“Psychiatrists should offer patients accurate information about their diagnoses, proposed treatments, risks, potential benefits and alternatives.”

—World Psychiatric Association Code of Ethics

“Hello, Mrs. Jones. Here to have the grenade explode inside your body? The doctor will be with you shortly.”

“Ahh, Ms. Lee! You’re right on time for your personhood removal. Second door to the right, please.”

Those nightmare scenarios are all too real for victims of electroshock, euphemistically referred to as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

“These survey findings lead us to recommend a suspension of ECT.”

Survivors often describe the terror in just such terms—like a cinder block being dropped on them, like an explosion in their heads and like losing parts of themselves.

And the United Nations calls ECT what it is: torture.

Passing an electrical current through the brain to trigger a grand mal seizure carries life-threatening risks—among them: brain damage, memory loss, cognitive impairment, cardiac arrest, even death.

Knowing that, who in the world would go within spitting distance of an electroshock machine?

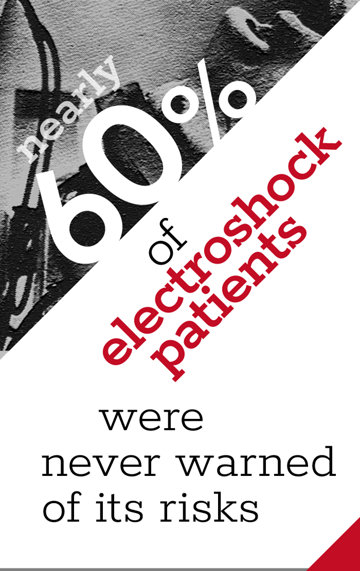

The answer, according to a recently released global survey of 1,144 ECT recipients and their family members across 44 countries, is that we don’t know.

Published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, the University of East London study—the largest international survey of its kind—reveals that:

- Nearly 60 percent were never warned by their practitioner of the dangers associated with ECT before being strapped down, anesthetized and subjected to up to 460 volts of electricity passing through their heads.

- An additional 17 percent were “not sure” whether or not they had been so briefed—a possible consequence of ECT-induced memory loss.

Just as striking was the nature of the study itself, wherein the researchers asked patients about their experiences with ECT. (You will search in vain for patient voices in most electroshock scientific literature.)

The verdict was damning:

- The majority reported that ECT either had no benefit or actively made their lives worse.

- About half said it made their lives “much worse” or “very much worse.”

- Two-thirds said it had a negative impact on their quality of life.

One can only imagine how many surviving victims, if given a second chance, would turn to the psychiatrist who prescribed them ECT and say, “No, thank you. I have no room on my to-do list right now for brain damage, cardiac arrest, amnesia or death.”

“These survey findings lead us to recommend a suspension of ECT in clinical settings pending independent large-scale placebo-controlled studies to determine whether ECT has any effectiveness relative to placebo, against which the many serious adverse effects can be weighed,” the researchers concluded.

Yet for more than four generations, electroshock has remained psychiatry’s go-to “treatment”—even as each press of the button risks death and suicide rates after “treatment” multiply sixteenfold.

And still, not one single “independent large-scale placebo-controlled” study exists that proves it works—let alone that it warrants such risk.

And the last one—small, inconclusive and, in University of East London Professor of Clinical Psychology John Read’s words, “methodologically inadequate”—was conducted in 1985, 40 years ago.

“The use of electroshock is outdated, dangerous and unnecessary.”

That’s 40 years of crickets while patients continue to be shocked without even the courtesy afforded those condemned to the gallows or the guillotine—knowledge of what awaits them.

Why the silence? Perhaps it’s because psychiatry is touchy about having its tracks uncovered. It dislikes being reminded that the cash cow it calls “therapy” actually kills.

Professor Read recalls his very first job as a clinical psychologist. A man had died on the ECT table the day before. When Read raised the issue at a staff meeting, the psychiatrist in charge erupted: “That is none of your business and I am personally insulted by your insinuation that we killed him.”

Read pointed out that the patient’s notes included: “ECT contraindicated—serious heart condition.”

For daring to tell the truth, he was physically removed from the meeting.

The mental health industry watchdog Citizens Commission on Human Rights International (CCHR), which has documented psychiatric abuses for more than five decades, pointed to the University of East London study as yet another confirmation of what its own investigations and one-on-ones with electroshock victims have long revealed: gross and routine violations of the right to informed consent.

Being told, “This will help you. You may be a bit groggy after—with just a tad of memory loss—but not to worry, you’ll feel so much better,” is not informed consent.

As Jan Eastgate, President of CCHR International, put it: “The use of electroshock is outdated, dangerous and unnecessary. On an immediate basis, Medicaid, Medicare, Tricare and state government insurance should stop coverage for this practice, the Food and Drug Administration should remove ECT devices from the market, and states should move to ban it outright.”

As it is, the only way psychiatrists seem willing to “inform” patients of electroshock’s dangers is by administering it to them.

Ernest Hemingway, before committing suicide shortly after receiving electroshock, remarked: “What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure, but we lost the patient.”