In that moment, Mothma is no longer just a character in a galaxy far, far away. She becomes a prophet of our here and now.

Because in 2025, truth is dying—not by censorship or brute force, but by proxy, by proxy author, by bots wearing smiles and surnames. By headlines written by code. And by the slow erasure of the very thing journalism once promised: a byline tied to a breathing human being.

“These practices violate everything we believe in about journalism.”

Across a growing number of websites, names like Nina Singh-Hudson, Leticia Ruiz and Eric Tanaka appear atop articles about crime, politics and tech trends. None of these reporters exist. They are AI-generated “personas” created by a company called Impress3 and assigned to write stories for Hoodline, a digital outlet that operates in multiple cities, according to a May 2024 article in Bloomberg News, titled “AI Fake Reporters Make It Harder for Readers to Tell Truth from Fiction.”

For a while, these “reporters” came with bios, headshots and folksy credibility. Their stories often paraphrased news statements or stitched together summaries from other sources—all the while making the material appear as though it was written by some journalist next door. There was no deception at first glance—only the faint feeling that something didn’t quite add up.

Zack Chen, Impress3’s co-founding CEO, sees no harm. In fact, he considers it innovation. “Each AI persona has a unique style,” he told Bloomberg News. “Some sort of ... personality style to it.”

His ultimate goal? That these fictional journalists might one day become “brands”—or even hosts of their own digital TV shows.

It would be almost charming, if it weren’t so chilling. “In trying to use a human-sounding name, they’re trying to game the system and taking advantage of people’s trust,” Hannah Covington, senior director of education content at the News Literacy Project, a Washington, DC-based nonpartisan education nonprofit, told Bloomberg News. Referring to AI’s increasing volume and reach, Covington added: “It’s important to remind people: Don’t let AI technology undermine your willingness to trust anything you see and hear.”

Few would doubt that Hoodline has actively “tried to fool its audience with fake writers” as Bloomberg contends. But what’s also clear is that what Hoodline did isn’t an anomaly—it’s part of a disconcerting and disturbing trend.

Sports Illustrated, the gold standard for sports journalism for decades, was found to have published product reviews under fictitious names with AI-generated headshots. When the news broke in November 2023, the Sports Illustrated Union, which consists of flesh-and-blood journalists who represent the legendary magazine’s staff writers, reacted with horror. “These practices violate everything we believe in about journalism,” the union asserted in a public statement, adding: “We deplore being associated with something so disrespectful to our readers.”

In Iowa, the former website of the Clayton County Register—a small-town newspaper founded in 1926—became a zombie publication. Its domain was quietly commandeered and repurposed as a clickbait factory, pumping out junk stock-market content written by bots. The original paper was absorbed in a merger. But the name still sold trust—and the bots were cashing in.

According to WIRED magazine, these fake sites can form sprawling networks of misinformation and propaganda, preying on search engine algorithms, unsuspecting readers and programmatic ad platforms that funnel money into their pages without a second thought.

A June 2024 report by NewsGuard, a respected journalism data analysis company co-founded and co-edited by former Wall Street Journal publisher L. Gordon Crovitz, put numbers to the chaos: AI-powered fake news sites now outnumber real local newspapers in the US.

Beyond the tech and the ethics lies something deeper: a psychic wound to the public square.

NewsGuard has identified 1,265 fake sites, 52 more than the 1,213 dailies left in the country. They look real enough. That’s the point.

Often they come with “About Us” pages, logos and fictional staff bios. The stories they publish may appear neutral at first, but their purpose can range from cheap engagement to outright disinformation—particularly in election cycles or politically volatile moments. Some are backed by partisans. Others by foreign actors. Some, simply by opportunists who understand the profitability of confusion as a business model—a strategic product manufactured and monetized not to just blur reality but paralyze discernment.

“This is massively threatening,” warns Sandeep Abraham, a former National Security Agency analyst turned digital investigator who, along with his former colleague Tony Eastin, raised concerns about misinformation and the erosion of trust in online media by uncovering that the Clayton County Register’s site was producing AI-generated clickbait under fake bylines. “We want to raise some alarm bells,” Abraham says.

Beyond the tech and the ethics lies something deeper: a psychic wound to the public square. The rise of AI-generated bylines represents not just a breach of trust but a dismantling of a centuries-old covenant between reporter and reader, rooted in the human act of listening and bearing witness. As the American Press Institute aptly puts it, journalism revolves around “the ability to hear, understand and recognize others’ needs and feelings”—a human responsiveness, whether at a kitchen table interview or a protest line, which forms the connective tissue between a reporter’s notebook and the public good.

After all, the moral force behind journalism—the element that gives a byline its weight—is not merely information delivery, but moral attention. This implies more than just reporting facts—it’s the deliberate, human effort to listen closely, interpret responsibly and convey with a sense of empathy, honesty and accountability.

AI, by design, does none of this. It does not recognize, it calculates. It does not understand, it correlates. It cannot assume ethical responsibility, feel indignation or extend compassion. An AI-generated article may replicate the structure of journalism, but it lacks the ethical presence of a journalist.

To entrust truth-telling to a disembodied entity incapable of moral discernment is to hollow out the covenant entirely—and to replace the act of reporting with something closer to mimicry than meaning.

So what happens when the “journalist” turns out to be a ghost in the machine? Or when a publication feigns journalistic credibility by posting stories under fake bylines featured next to deceptive photos of reporters that don’t exist?

That was precisely the case with Distractify, a Florida-based digital media outlet known for viral content and tabloid-style reporting, which came under fire for quietly altering a byline after public backlash.

On March 11, the site published an inflammatory, fact-free piece attacking the Church of Scientology, penned by freelancer Jennifer Farrington. But after STAND League, an organization devoted to fighting anti-religious defamation and bigotry, condemned the article as bigoted disinformation, Farrington’s byline was stealthily replaced with the name “Reese Watson”—a persona with no online presence and a stock photo that had also been used to promote dermatology and Invisalign services in Southern California.

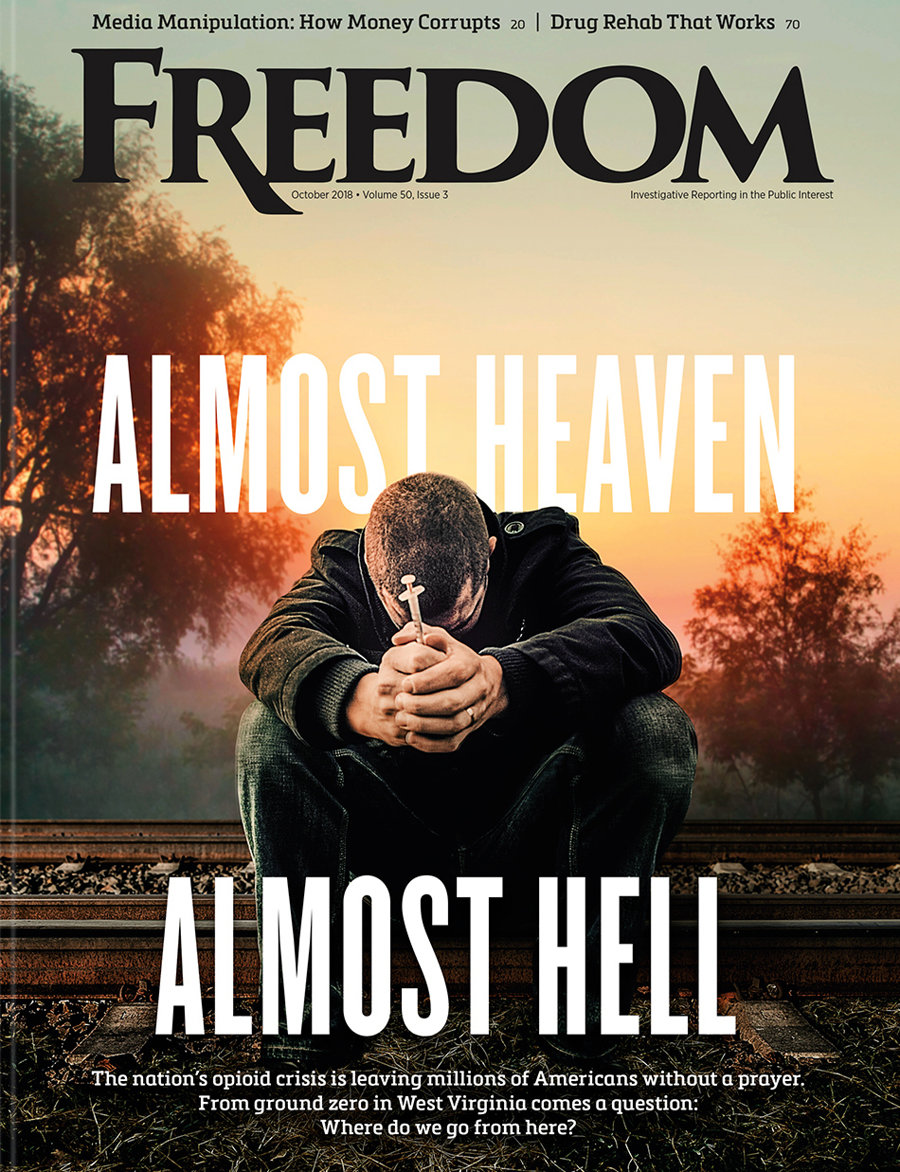

The situation escalated when Freedom exposed the swap in an April 13 report, prompting further scrutiny of Distractify’s editorial practices. Senior editor Carly Sitzer, whose name appeared on the site until April 20, claimed she had left the company months earlier. Yet her presence on Muck Rack and on Distractify’s own pages told a different story—one that raised even more questions about transparency and accountability in digital journalism.

In distant Australia, freelancers and contributors to Cosmos Magazine recently discovered that their own articles had been used to train an AI tool that is now producing science explainers—without their consultation or consent. Some are calling it theft. Others, a betrayal of the very role journalists play in separating noise from signal.

Meanwhile, headlines hallucinated by AI swirl through social media, picked up by aggregators and shared by millions. Readers are left trying to distinguish between fact and fakery while the originators remain masked behind code and “personality.”

So what’s left?

Journalism, at its best, is a human act—an imperfect, purposeful attempt to chronicle what’s real. When done right, it’s carefully conceived, reported, painstakingly written and fact-checked. It’s attributed. It’s signed. But if the byline dies—if we stop caring who’s speaking or whether they even exist—then what rises in its place is not just a crisis of credibility. It’s a cultural void that creates a society no longer capable of distinguishing between what is said and what is true.

In Andor, Senator Mon Mothma calls it the death of truth. Today, it’s not just a metaphor—it’s a reality. It even has a sound: the hum of that all-pervasive algorithm behind your next headline.