“Nonaddictive” declaration set the stage for opioid crisis.

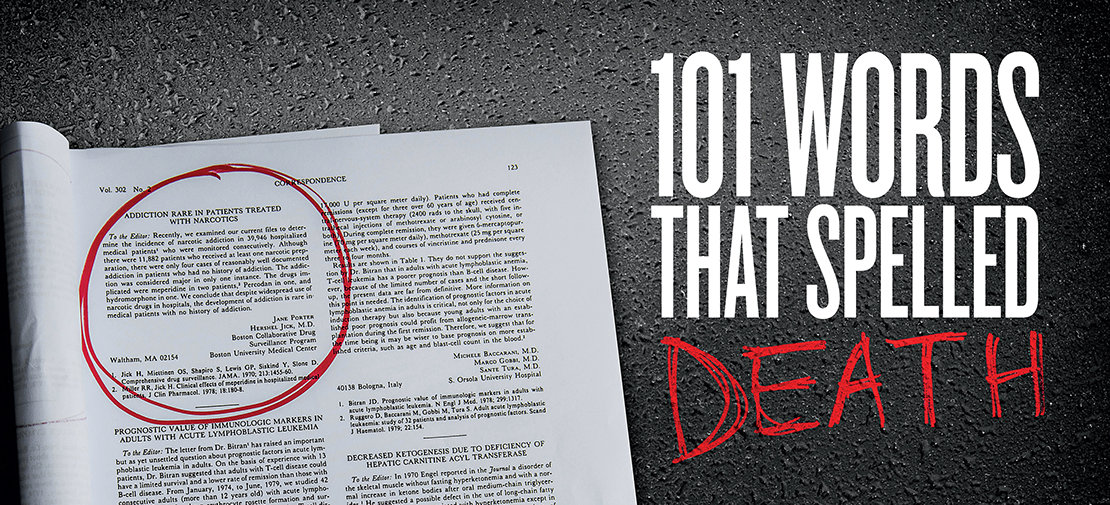

The worst drug crisis in American history started with a single paragraph—a five-sentence “Letter to the Editor,” published in small type, on page 123, near the back of a prestigious journal.

The 1980 letter, now known as the “Porter and Jick” letter, was printed under the authoritative-sounding headline: “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.”

“To the Editor: Recently, we examined our current files to determine the incidence of narcotic addiction in 39,946 hospitalized medical patients who were monitored consecutively. Although there were 11,882 patients who received at least one narcotic preparation, there were only four cases of reasonably well documented addiction in patients who had no history of addiction. The addiction was considered major in only one instance. The drugs implicated were meperidine in two patients, Percodan in one, and hydromorphone in one. We conclude that despite widespread use of narcotic drugs in hospitals, the development of addiction is rare in medical patients with no history of addiction.”

This “proof” about opioids and addiction offered by this 101-word letter would go on to be cited in more than 600 medical and pharmaceutical publications and used for innumerable marketing campaigns. The claim that opioid addiction was rare, fueled a series of events which snowballed into the opioid epidemic.

This green light for the gross overuse of opioid pain medication apparently began innocently, when Boston University Medical Center’s Dr. Hershel Jick began looking at addiction. Jick, a respected drug specialist, asked a graduate research student, Jane Porter, to help calculate how many patients in the database had become addicted after being treated with pain medicines.

After her review of cases, she dashed off a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Its brevity was grotesquely disproportionate with its morbid effect.

Based on Ms. Porter’s review of nearly 12,000 cases, it may have been reasonable to infer that narcotics, including opioids, offered little chance of addiction, among hospitalized medical patients who were monitored closely, with no history of addiction.

But this hastily compiled letter—not an article, not an editorial, but a letter—would soon be trotted out as reliable evidence that anyone in any circumstance who took any amount of opioid pain pills stood almost no chance of becoming addicted.

The conclusions contained in the letter would be misrepresented in medical journals and throughout pharmaceutical marketing documents, with an unexplained logic that the letter was itself evidence that addiction to opioids was rare in any circumstance—ignoring the numerous mitigating qualifiers for that assumption.

“Despite widespread use of narcotic drugs in hospitals, the development of addiction is rare in medical patients …”

Boston Collaborative

Drug Surveillance Program, 1980

“This pain population with no abuse history is literally at no risk for addiction,” one citation said. “There have been studies suggesting that addiction rarely evolves in the setting of painful conditions,” said another.

Purdue Pharma and other pharmaceutical companies held “pain clinics”—which were really paid parties—for doctors and pharmacists, convincing them this “evidence” showed that not treating pain with opioids was practically unethical. Doctors were taught, critics now say, to think of pain as the “fifth vital sign,” and that pain pills were the only solution.

Purdue released an OxyContin promotional video in 1998 featuring Dr. Alan Spanos, who said, “In fact, the rate of addiction among pain patients who are treated by doctors is much less than one percent. They do not have serious medical side effects,” he added.

These claims, later exposed as lies, opened Pandora’s box and became the lever needed to unleash an unlimited supply of killer opioid compounds on an unsuspecting public.

The result has proved tragic.

Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP) interviewed physicians in 2016 on camera talking about assurances by drug marketers that opioids were safe. Dr. Andrew Kolodny, now the executive director of PROP, said he had been taught that “instead of allowing patients to suffer needlessly, we should be much more liberal in our prescribing of opioids.”

Dr. Nathaniel Katz said he was taught that “pain soaks up the euphoria, and therefore you can’t become addicted to opioids.” He added that if you look at the “less than one percent” promotional materials, you’ll often see mention of the Porter and Jick study, and some similar-quality research, used as a reference. “But one has nothing to do with the other,” he said.

“It was a gross misinterpretation. Not just by the manufacturers, by the way, but by the so-called ‘thought leaders’ who were in positions of eminence in some of our professional organizations … who allowed that myth to perpetuate itself.”

One of those thought leaders is Dr. Russell Portenoy, who the Wall Street Journal once called “the Pain Doctor.” His seminars at the time encouraged the use of opioids to treat all pain, though he later reversed his opioids-for-everything approach. He has since complained that doctors were improperly led to believe patients in real pain “could take a potentially ‘abusable’ drug, and the risk of addiction is minimal to nil,” he recalled on the PROP video, now posted on YouTube. “That’s completely incorrect.

“Clearly, if I had an inkling of what I know now then, I wouldn’t have spoken in the way that I spoke,” Dr. Portenoy said.

Recently, long after Purdue Pharma’s 2007 guilty plea to federal charges of intentionally misrepresenting the addiction likelihood of its opioid pain pills, the NEJM released results of a new study, a bibliometric analysis of articles citing the Jick/Porter letter.

“It’s difficult to overstate the role of this letter,” said Dr. David Juurlink of the University of Toronto, who led the analysis. “It was the key bit of literature that helped the opiate manufacturers convince front-line doctors that addiction is not a concern.”

The study notes “a sizable increase” in citation of this “evidence” after the introduction of OxyContin in 1995. The original letter “was leveraged as proof that opioids could be used safely over the long term, even though it offered no evidence to support that claim,” he said.

The New England Journal of Medicine has taken the rare step of adding an editor’s note in its online archives which accompanies the original issue. It states: “For reasons of public health, readers should be aware that this letter has been ‘heavily and uncritically cited’ as evidence that addiction is rare with opioid therapy.”